> Knowledge hub > Psychological safety and the importance of safe leadership

> Knowledge hub > Psychological safety and the importance of safe leadershipPsychological safety may seem like a complex academic subject at first, but it’s actually quite simple when you boil it down to the essentials.

Amy Edmondson from Harvard University is a pioneer in the study of psychological safety. She describes psychological safety as a person’s perception of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in the workplace. It encompasses taken-for-granted beliefs about how others will react if you expose yourself in situations such as asking a question, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake or suggesting a new idea.

In moments like these, we make microsecond calculations to assess the risk and likely consequences of our behavior. We make these decisions against the backdrop of the interpersonal climate we find ourselves in and say to ourselves: “If I do X here, will I be hurt, exposed or criticized? Or will I be praised, thanked and respected?”

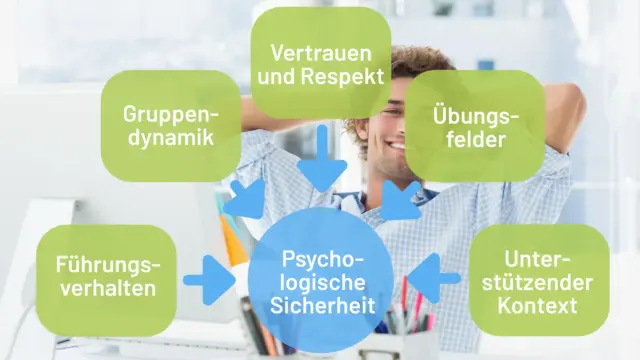

There are five areas that contribute to the creation of a psychologically safe environment. The first is the behavior of the manager. Leaders are always in the spotlight. What they say and do has a profound impact on whether team members feel safe enough to open up. Research has shown that bad news is rarely shared upwards and that team members are more likely to seek help from colleagues than from their managers. On the other hand, studies also show that leaders who demonstrate supportive behavior have a positive effect on self-expression and creativity. Managers need to make a special effort to be open and demonstrate coaching-oriented behavior. The three most effective behaviors that promote psychological safety are:

The second area is group dynamics. The norms of a group encourage or inhibit the vulnerability of team members. Are new ideas welcomed or discouraged? Are divergent opinions sought or criticized? The interplay of team roles and characters is also part of the group dynamic. In-group and out-group dynamics and the distribution of power among team members also influence psychological safety.

The third area that influences psychological safety is trust and respect. There is a significant overlap between trust and psychological safety in terms of vulnerability. Trust can be defined as the willingness to be vulnerable because of the perception of the trustworthiness of a person or thing. If there is a lack of trust in the leader or team, people will not want to take risks. Supportive and trusting relationships promote psychological safety, whereas a lack of respect leads to people feeling judged or inferior and keeping their opinions to themselves.

The fourth area is the use of practice fields. Peter Senge coined this term in the 1990s to describe one of the characteristics of a learning organization. Unlike in other areas, many companies do not use practice and reflection to improve the skills of their employees. Practice fields create a safe environment to learn, make mistakes and work on improving skills without fear of punishment.

Finally, a supportive organizational context contributes to psychological safety. This means that team members have access to resources and information to perform at their best. When people have this kind of freedom, it reduces anxiety and defensiveness.

Psychological safety is a benefit for both employees and the organization. Safe environments encourage people to seek feedback more often. A culture of psychological safety also encourages innovation. Ultimately, psychologically safe environments allow team members to collaborate more effectively across departmental boundaries.

It is critical that leaders create an environment of trust and safety so that their team members can excel, step up and reach new heights of success. It starts with being a confident leader who is trustworthy, respectful and puts the well-being of their team members above their own interests. It starts with trustworthy leadership.